Palimpsest

Three and half millennia ago, a man chips at a stone with a bronze hammer, eying the edges to best fit the wall of the house he is raising. Sweating in the upland sun …

Not far from the modern city of Sparta, a prehistoric settlement of small stone houses clusters round a Mycenaean mansion occupied in the thirteenth century BC. Nearby stands an ancient altar, on a hill from which the view of surrounding mountains is the same today as that observed by Bronze Age builders; there, Helen of Troy and her forbearing husband were worshipped. Storytellers would remember Menelaus as king of Sparta, and his unfaithful wife as the cause of the war against Troy.

Hero cults, so far as we know, date back only to the eighth century BC, about the time that the poems we attribute to Homer are thought to have been formalised – centuries after the collapse of the society they describe. The structure visible on the hill today is the last in a sequence of three stone temples built over the course of three hundred years. In its ruins have been found votive gifts inscribed to Helen and Menelaus.

Temples stand on stories, tales are born of misinterpreted ruins. Some are scraped away, others are recycled, and in some the stories merge.

… he cannot imagine, a thousand years later, the mason who carves his section of architrave for a temple to another god. In the clamour of the stone yard on the headland above the bay …

Perched like an eagle on the city’s acropolis, Athena’s temple is as faceless as a cliché – a postcard image, its builders’ uncanny intentions invisible to most. Determined to maintain her dignity in a sea of scaffolding and selfie sticks, the Parthenon offers the crowd the show it expects: white marble columns between a stone sandwich of stylobate and carved architrave, the latter still decorated in places with sculpted metopes. Her audience suspends its disbelief for the duration of the visit and does not know it’s being hypnotised: oblivious to the variations that make the marble seem almost to levitate, no more aware than it is of the hidden corset that gives an actor her convincing shape.

Exquisitely subtle, the upward curve of the temple platform and architrave, the outward bulge of the fluted columns, the inward lean of the entire colonnade all lift the building, and the voids are as carefully calculated, as mathematically modulated, as the solids. Columnar gaps deviate by no more than a millimetre, and the seams between the slabs of the stylobate are less than the width of a human hair. The ancient Greeks were a seafaring race, a people practiced in boatbuilding. They knew how to gauge the curve of a keel and the swell of a hull, and they understood the critical importance of fitting each element precisely. What works in wood is refined in stone.

Between the Parthenon and the pretty Erechtheion lies a field of marble blocks – the footprint of an older building, its stones now randomly juxtaposed. The Old Parthenon hugs the ground like Athena’s owl, in the spot where a Mycenaean palace probably stood. Stones from the Bronze Age complex were surely reused in that shrine, just as its blocks became part of the platform for the Periclean temple. And so it goes.

… the master mason cannot not imagine, five hundred years later, the apprentice stoneworker who squares the edges of a slab of red-veined marble that will finish a wall inside a vast building – a new one, built in the Roman style. The young man’s arm judders with every bite of his chisel into the stone, each mark as personal as a brushstroke …

Six centuries after the politician Pericles apportioned funds for a new Parthenon, the emperor Hadrian resolved to refurbish his favourite city. At the edge of the new forum, below the acropolis rock, he would build a library. It would be, in the Roman way, a building as beautiful inside as it was elegant outside: foliate capitals and brightly painted architraves, and interior walls faced with alabaster and fine marble veneers in green, red and black stone. Pausanias, on his tour of Greece in the second century, described for his readers halls with painted ceilings and niches with colourful statues; monoliths in green Karystos marble marked the entrance, and the internal colonnade comprised a hundred columns made of creamy Phrygian marble with purple veins.

Clearing the ground for construction meant sweeping away the Greek and early Roman houses that occupied the spot – with, presumably, their occupants. Three centuries later the same fate befell the library itself, when the local leader of a new religion decreed that this would be the place where Athens’ first Christian church would stand.

… and he cannot imagine, thirteen hundred years later, the painter who quietly conjures the face of a saint on a freshly plastered wall. Outside the new church an olive sapling grows …

On the slopes of Mount Taygetos in the southeast Peloponnese, a ruined city preserves twelve churches. The fresco cycles that still decorate them tell the stories of the Holy Family, martyrs and saints, heaven and hell. The time of their creation is referred to as the Palaeologan Renaissance, after the ruling dynasty – a final flowering of commercial, intellectual and artistic culture, when the churches and their town were renowned across the late medieval world for cosmopolitan humanism. The site has neither precursor nor progeny: it was founded on virgin ground in the thirteenth century and abandoned in the nineteenth, leaving the Byzantine ruins all but untouched except by the forces of decay.

Ghosts have been known to walk the streets of Mystras, spotted on rare occasions when a visitor escapes the other tourists to find himself solitary – and then not. He learns that ghosts are not just apparitions, not merely a young woman in medieval peasant dress hurrying out of sight round the corner of a crumbling house. The clop of a donkey’s hooves on the cobbles and the smell of incense and manure materialise as suddenly as the figure, and hold … until the sound of a bus revving below breaks the spell.

… inside, the artist cannot imagine that five hundred years later his work will be defaced by a man like him, in the name of yet another god. The assailant stabs at the eyes of the saint before aiming his hammer at next image, of the angel Gabriel …

At the highest point within the walls of the fortress of Acrocorinth, overlooking the Corinthian Gulf, stood a temple of Aphrodite, now marked only by a single column. The temple was said to be a centre of ritual prostitution, as a result of which the city below gained a reputation for immorality and licentiousness. It is said by some that Saint Paul preached here on his visit to Corinth, and he doubtless would not have approved of the habit among some modern visitors of paying homage to the ancient god on the spot of her temple in the most appropriate way.

In the normal way of sacred shrines, the temple became a church, and later a mosque, the Christian paintings first lacerated then whitewashed over. The Ottoman occupants of the fortress often included foreign subjects, refugees from even less salubrious lives, including Syrians whose ancestors worshipped Aphrodite as Astarte, goddess of fertility, guarantor of continuous renewal.

… and he cannot imagine that two centuries later the olive sapling, now ancient, shades me.

Ancient Greek writers referred to a surface that had been scraped clean, ready for reuse, as παλιμψξοℜοs, a palimpsest. It is from this sense that its dictionary definition is derived: a page of medieval parchment from which one written text has been removed to make room for another. The term originally implied not layering, but erasure – clearing away, not accumulating. In the way of time, the word has gathered accretions, and today it is as often understood as a sort of collage, comprising layers of experience, of occupation, of processes.

A palimpsest may be understood as the physical manifestation of cultural or personal memory. Sometimes the recollections retain their separation, layer on layer, and sometimes a crack in the upper strata reveals evidence of earlier deposits. At other times it is the last layer that is removed, leaving a ghostly footprint of what came after within the warp of earlier events. And sometimes, as with art, the layers fuse, creating something new.

—Diane Fortenberry

Diane Fortenberry, a native of Jackson, Mississippi, lives and writes in London and Athens.

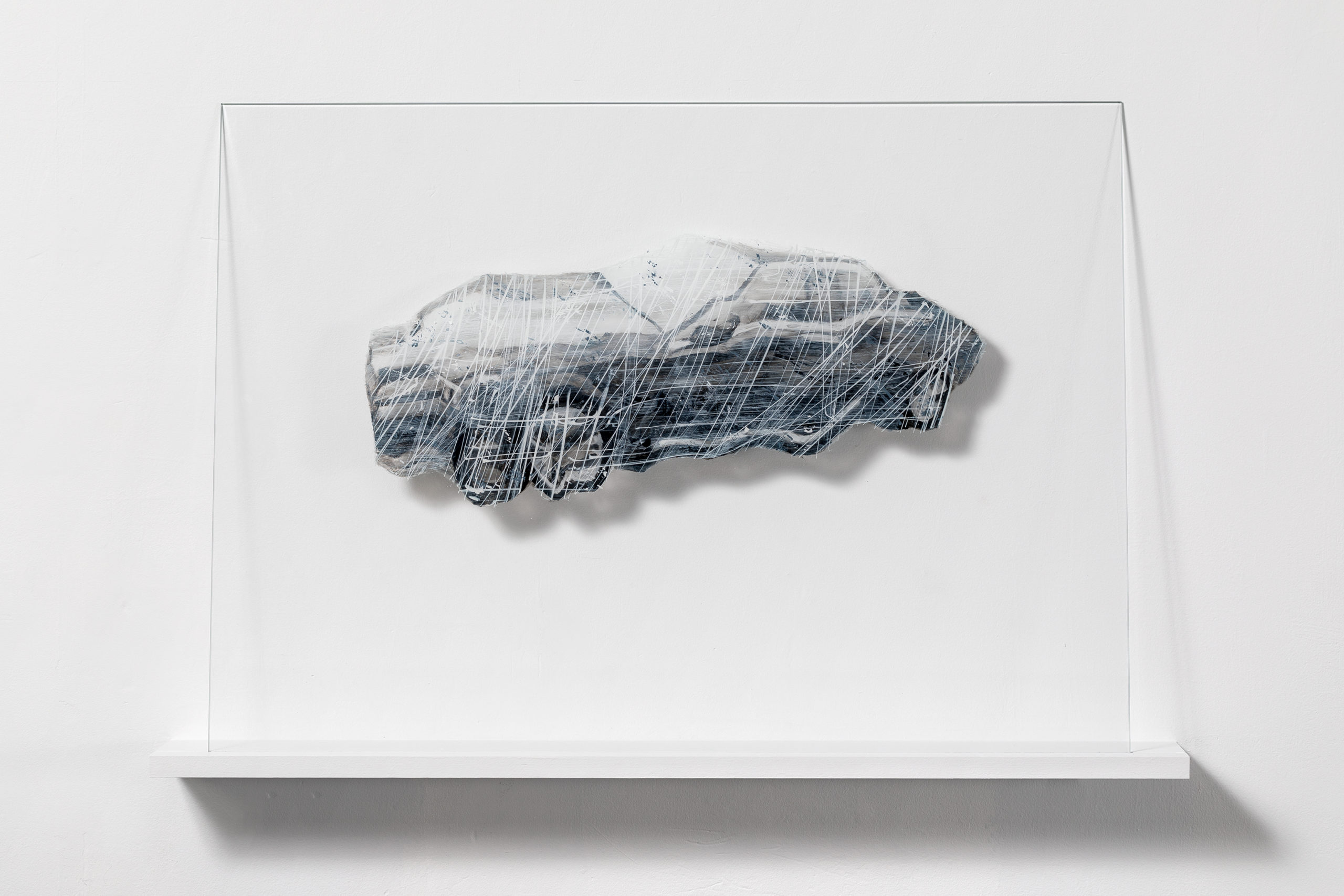

Mary MacDougall (b. 1983, Australia) is interested in the physicality of paint, subjects in transition and questions of perspective. She works with glass, ceramics and image archives. Forms in her work sometimes appear ancient and quiet, while at other times like super-heated rock, flowing and coagulating.

In a new series of paintings, R.B. Waves, sheets of industrial glass are used as a medium for reimagining the image making process. Layers of paint are built up on the reverse of the glass, making evident the construction of a range of disparate forms with delicate string like textures and gradations of transparency. Distorted cars, fragments of ancient statuary and figures set in motion, are woven together with a mass of lines and then compressed under glass like painted specimens.

Mary MacDougall lives and works between Sydney and New York. She regularly contributes to various journals, has performed in The Bowles (2008), was a Helen Lempriere Scholarship finalist (2009), released The Bowles EP on Graham Lambkin’s Kye record label in New York (2012), has exhibited widely in artist run spaces in Sydney, Melbourne and San Francisco and participated in group shows at Breenspace, Sydney and Minerva, Sydney.

Forthcoming publications are in development with Reading Room, Melbourne and Cooperative Editions, New York.

MACDOUGALL, MARY. R.B. Waves, ReadingRoom, Melbourne, 26 May–7 July 2018

Mary MacDougall, R. B. Archipelago, Cooperative Editions (Co-Ed), New York, 2017

Mary MacDougall, Raft Amphibians, Cooperative Editions (Co-Ed), New York, 2017

http://rbiscuitjournal.tumblr.com/

With thanks to Ivan Ruhle, Diane Fortenberry, Wendy Gray, Hana Shimada, Anna John and Koji Ryui